Labor Secretary: 64% of Newly-Unionized Units Fail To Obtain Agreements Within One Year

“There is no schedule or process for reaching an agreement, and bargaining can drag on for years.” — U.S. Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh

With union organizing activity having increased significantly over the past year, only a minority of newly-unionized bargaining units will obtain labor contracts within one year, according to a recent op-ed written by Labor Secretary Marty Walsh.

“There is no schedule or process for reaching an agreement, and bargaining can drag on for years.” — U.S. Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh

In an op-ed published in the Seattle Times, Secretary of Labor Walsh advocated for passage of the Protecting the Right to Organize Act (or ‘PRO Act’)—which calls for government-imposed binding arbitration if parties cannot reach an agreement within 120 days— by using the following statistics as an argument for the PRO Act’s passage:

“There is no schedule or process for reaching an agreement, and bargaining can drag on for years. And it’s getting worse. Twenty years ago, nearly half (48%) of all newly organized units reached a first agreement within a year, and nearly two thirds (63%) within two years. But today, only 36% of newly organized units reach a collective bargaining agreement within one year, and only 58% after two years.” [Emphasis added.]

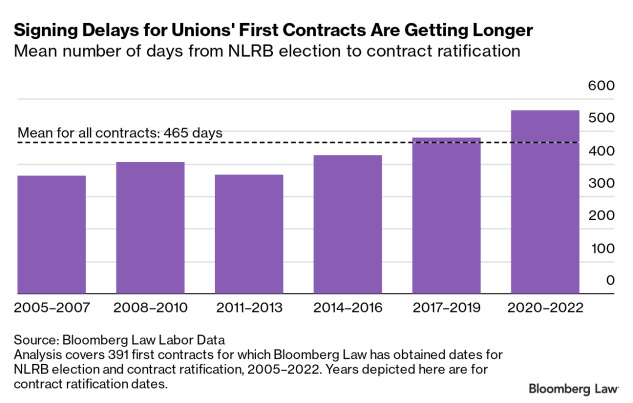

Although the PRO Act is not likely to be made into law anytime soon, Walsh’s statistics seemed to correspond Bloomberg Law’s analysis earlier this year that stated the mean number of days it takes to negotiate a first-time contract is 465 days.

While unions and their allies often point at companies that may be purposely delaying the reaching an agreement, there are also other factors that cause first-time (or ‘initial) contract negotiations to take much longer than successor agreements, as first contracts involve negotiating contract “language” for the first time.

Additionally, from a union’s perspective, unions try to achieve the best deal possible for its members and, likewise, an employer does the same for its business. If there is a single clause, or multiple clauses, where the parties do not see eye-to-eye, that will often cause delays that can last months or years.

When Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, it required employers and employee representatives (normally unions) to collectively bargain in good faith” with regard to “wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment.” However, as written, the law did not require the parties to agree to a contract.

In fact, Section 8(d) of the Act specifically states the obligation to bargain “…does not compel either party to agree to a proposal or require the making of a concession…”

While there have always been instances where employers and unions simply cannot reach agreements, and those numbers have increased over the last several decades, there remains strong debate as to whether the federal government should be used to impose contracts on disputing parties, as the PRO Act’s binding arbitration provision would do.

While this business community has long opposed imposed contracts, similarly, rail workers this week are finding themselves opposing Congress’ intervention of imposing collective bargaining agreements they had rejected.

So, while negotiations for first contracts may be taking a longer time than decades ago, perhaps having the government interfere is not the answer.