Labor Relations 101: How 'Quickie Strikes' Turn Into Lockouts

Lockouts and post-strike lockouts are (mostly) lawful.

By Peter List, Editor | June 23, 2024

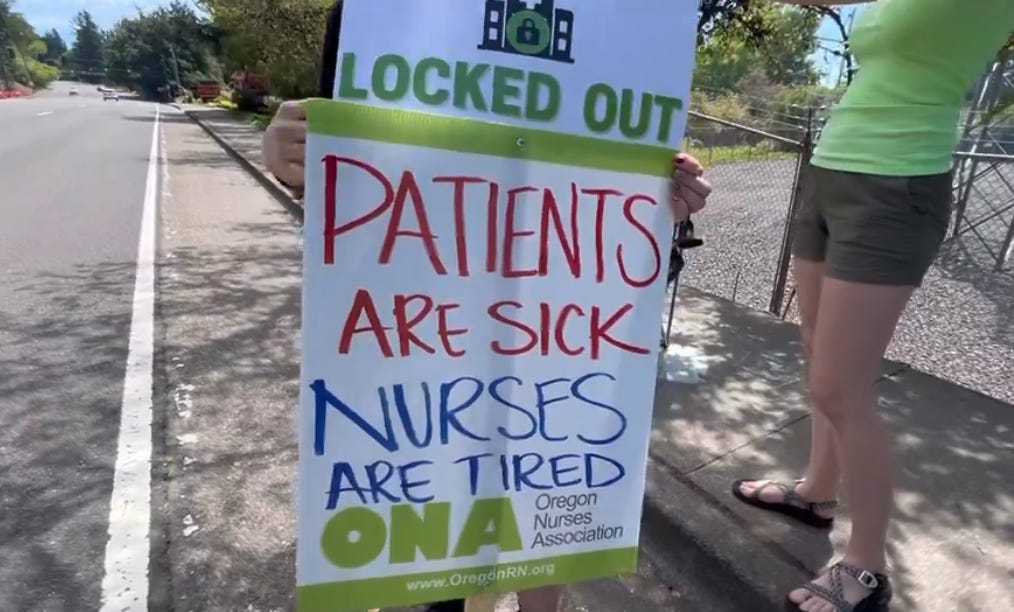

Last week, approximately 3,000 nurses represented by the Oregon Nurses Association (ONA)—affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers—went on a three-day strike at six Providence Health facilities across Oregon.

“The strike comes after more than six months of contract bargaining between Providence and the nurses' unions at each facility, including federal mediation, in an effort to avoid a strike,” reported KGW8.com.

As often happens with strikes in healthcare, Providence Health hired replacement nurses to staff the hospitals and care for patients.

However, on Friday, when the unionized nurses went to return to work, the replacement staff stayed and Providence Health locked the striking nurses out for an additional two days.

Immediately, the ONA declared the lockout was “illegal.”

As strikes and lockouts are the “economic weapons” used by unions and employers, respectively, the ONA’s declaration that the lockout is “illegal” may be flat-out wrong.

Here’s why…

From strike to lockout

In healthcare, when unions call staff out on short strikes (sometimes referred to as “quickie strikes” due to their short duration), it is very common for the employer to bring in replacement staff to care for patients.

Usually, the companies that provide replacement staffing services contract on a weekly basis. This, apparently, was also the case with Providence Health.

“Union leaders knew there would be a five-day replacement period,” Gary Walker, a Providence spokesman, told the press.

The company hired temporary nurses on five-day contracts. Walker said if the hospitals need any staff nurses to return on Friday or Saturday, they would contact them. [Emphasis added.]

When the striking nurses went to return to work, they had to stay out for another two days.

“This is illegal because ONA gave notice that nurses would return to work at 6 a.m. on Friday, June 21st,” the ONA stated. “Our nurses have a right to return, and the employer has to immediately reinstate them by law. Providence is refusing to do that, and that is illegal.”

On this, unless there is some unknown factor that would cause the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to rule the strike an unfair labor practice (ULP) strike (as opposed to an economic strike)1, the ONA is mistaken.

Lockouts are (mostly) legal

In labor disputes, strikes are considered a union’s ultimate economic weapon.

On the other hand, though, “Lockouts are the inverse of strikes: the employer refuses to allow workers back on the job until the union signs a contract on the employer's terms,” as this Labor Notes’ strike manual states.

There are offensive and defensive lockouts, as Labor Notes explains here:

Q. When can an employer declare a lockout?

A. In the early years of the National Labor Relations Act, lockouts were allowed only for “defensive” purposes—to prevent sabotage by the union, for example. But in 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court said an employer could lock out employees “for the sole purpose of bringing economic pressure to bear in support of his legitimate economic position.”

An employer can declare a lockout when the contract expires, in reaction to a union’s “inside campaign,” or when a union offers to return from a strike. An impasse in negotiations is not a prerequisite.

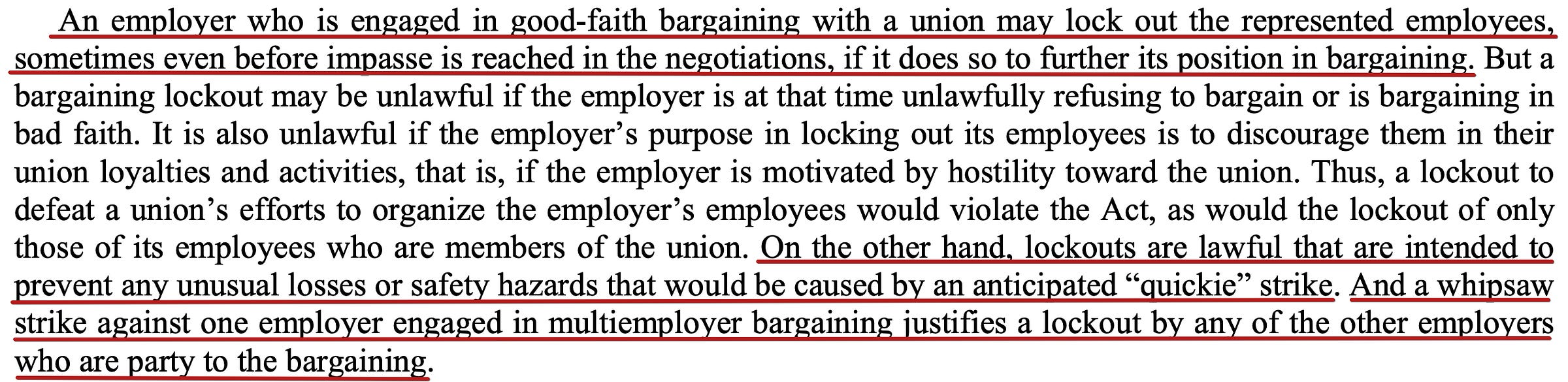

Here is how the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) explains lockouts (p. 19, in PDF):

As the lockout comes on the heels of a “quickie strike,” the Providence Health lockout of the ONA nurses is not a pure lockout. In other words, it is a post-strike lockout and only done as the healthcare system was obligated to replacement staff for five days’ worth of work.

Post-strike lockouts in healthcare not out of the norm

In the case of the ONA at Providence Health, unless there are some unknown factors to convince the NLRB that Providence Health was motivated by union animus, it does not appear to have done anything out of the norm.

For example, in response to a nurses’ strike in Texas in 2023 at Ascension Seton Medical Center Austin, nurses were informed that “they would be locked out for an additional three days following their planned one-day strike because the staffing agency that the hospital used to supply temporary nurses requires a four-day minimum contract.” [Emphasis added.]

Similarly, in response to a one-day California Nurses Association strike in 2022, Sutter Health locked striking nurses out for an addition four days.

"When the union threatens a strike we must make plans that our patients, teams and communities can rely on," a Sutter Health spokesperson told the press at the time. "Part of that planning is securing staff to replace nurses who have chosen to strike, and those replacement contracts provide the assurance of five days of guaranteed staffing amid the uncertainty of a widespread work stoppage." [Emphasis added.]

In Oregon, where the ONA-represented nurses returned to work on Sunday, the parties still do not have a contract.

This means, of course, the ONA may call another “quickie” strike at some point in the future and, if Providence Health has to bring in replacement staff again to care for patients, the same thing could happen all over again.

Even in the unlikely event the NLRB were to rule the three-day strike was a ULP strike, Providence Health would not have to take the nurses back immediately (though it could have some back bay liability for the two days nurses were kept out).